Nowadays, one can be forgiven for taking peripherally wound automatic calibers for granted. There are quite a few of them in production, after all. But until fairly recently, that wasn’t the case. For quite some time, there weren’t any in production – from 1985 to 2008, in fact. We can look to Carl F. Bucherer as the manufacturer that revived a genre that had gone dormant in the ’80s. In the twelve years since the company’s CFB 1000 was announced, what had been viewed as a difficult mechanism to industrialize has become a technology that’s been successfully paired with a fairly wide range of complications. Below, we can see a nicely decorated example made by Breguet. It enables a full rear view of its tourbillon mechanism.

One of the other operators in this arena that springs readily to mind is Vacheron Constantin, part of the Swiss old guard if there ever was one. As with Breguet, Vacheron also uses its peripheral winding system to power a tourbillon that can be seen from both sides. And there have been quite a few others who have made use of peripherally wound movements. Just taking the letters A, B, C, and D, we have Audemars Piguet, Bulgari, Cartier, and DeWitt. In late 2017, Piaget used a peripheral rotor to set the record for the thinnest automatic watch with the 4.1mm-thin Altiplano Ultimate 910P, below.

At its launch, Carl F. Burcher’s aforementioned cal. A1000 movement – which was announced in 2008, presented at Basel 2009, and made possible by the acquisition of Téchniques Horlogères Appliquées back in 2007 – was not only Carl F. Bucherer’s first in-house peripheral automatic caliber, but its first in-house caliber of any kind. It was an interesting place to start, to say the least, and one that evinced an impressive level of ambition and watchmaking chops. Since then, CFB has leaned into the peripheral rotor; it’s become a defining aspect of its collection of in-house movements. Most recently, CFB built upon this experience by making its own peripherally winding tourbillon which, you guessed it, is also its first in-house tourbillon.

Bulgari has also been a very prominent user of peripherally winding movements. It used one to beat Piaget’s 2017 record for thinnest automatic watch. At 3.95mm thick, Bulgari’s Octo Finissimo Tourbillon Automatic wasn’t just the thinnest automatic watch when it launched in 2018, but also the thinnest automatic tourbillon and the thinnest tourbillon – full stop.

Bulgari also drew on a peripheral winding mechanism to break a 32-year-old Frederic Piguet / Manufacture Blancpain record for the thinnest mechanical chronograph in the world when it released the Octo Finissimo Chronograph GMT in 2019. As we’ll soon see, the peripherally wound movement was created with thinness as its main objective, and Bulgari and other brands have certainly used it to that end. Nowadays, it’s equally employed as a way to afford unobstructed views of automatic moments – there’s no pesky full rotor to get in the way.

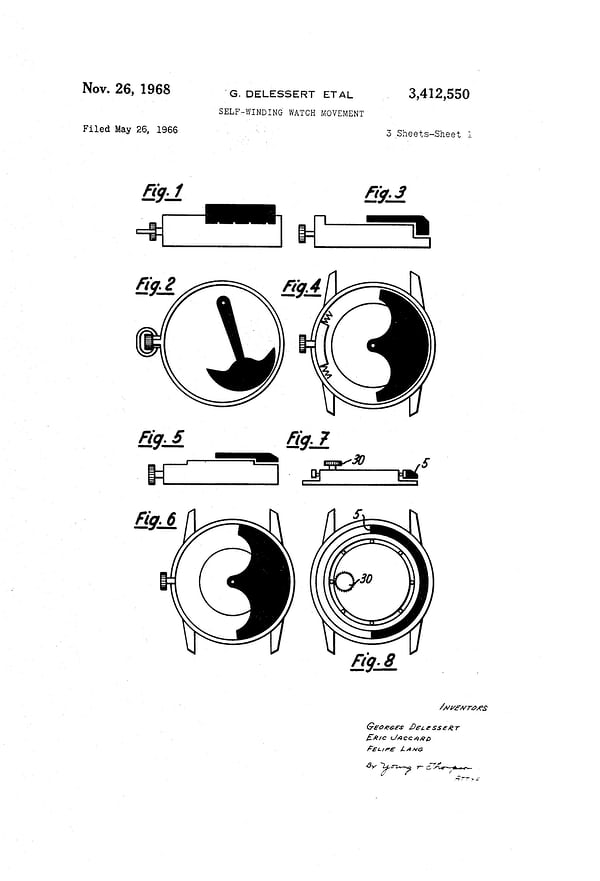

But if you follow the road back to the first peripherally winding movement, as with so much in horology, it leads to Geneva and the house of Swiss made fake Patek Philippe, which made quite a few of them in the 1970s and ’80s – thousands, in fact. And yet, they’re not particularly well known today. I learned of their existence earlier this year in the course of fact-checking an article on Carl F. Bucherer. After filing a patent for a self-winding movement in 1965, Patek Philippe pursued its peripheral-winding movement project for a number of years. In 1969, it came out with the cal. 350. In 1979 came an improved version, the cal. I-350. The “I” stands for “improved.” The I-350 was made in about 10,000 units, according to Watch Wiki, until it was finally retired in 1985, along with, it seems, Patek’s peripheral-winding ambitions. The earliest patent for a peripherally winding movement is attributed to the Swiss watchmaker Paul Gosteli and dates from the mid-’50s.

Why are calibers 350 and I-350 not as famous as some of the other automatic movements that Patek developed around the same time? One of the main traits of Patek Philippe’s peripherally wound watches was their unusual placement of the crown on the back, earning them the nickname “backwinders.” The positioning of the rotor precluded the crown, stem, and keyless works from being placed where they traditionally go. One will sometimes notice in photographs of Cal. 350s that they look a bit dirty, even for an old watch movement that may not have had a cleaning in a while. This is likely because the crown placement offered a pathway for moisture from the wrist to enter the case. One will also notice that, despite the fact that cal. I-350 bears the Geneva Seal, it is actually fairly plain-looking.

These movements were developed long before the days of the see-through caseback. And while the peripherally wound movement today seems, and is, tailor-made to be viewed through a disc of sapphire glass, cal. I-350 was designed with a different order of priorities. They were made, in the main, to be thin, if not exceptionally beautiful, and to offer a compelling alternative to quartz in the age of the Beta 21, the pioneering Swiss-made quartz movement.

Consider, too, the state of the Swiss watch industry in the ’70s and early ’80s. “It was a period of upheaval for Swiss watchmaking and profits were under pressure,” Eric Wind, the proprietor of Wind Vintage told me. “I see a lot of these backwinders in steel, which is cool, but obviously this was less expensive for Patek at the time.” Wind went on to tell me that the watches are difficult to sell today.

John Reardon has a more positive view of the cal. 350 and I-350, saying that he feels the movements’ poor reputation is probably unfair. Formerly of Christie’s and perfect Patek Philippe replica, Reardon’s is a name that, like Wind’s, longtime HODINKEE readers may remember from his HODINKEE byline. He now operates the site Collectability. “But the 350 is a beautiful movement; the 240 [a well-known Patek movement which saves on thickness in a different way, with a micro rotor], however, is simply far superior in terms of functionality,” Reardon told me. “Cal. 350 was a canvas for design, an automatic alternative to quartz for watches that were very focused on dials, textures, and classic shapes. The functionality is quite literally on the back. The lack of a crown on the side enabled Patek Philippe to explore designs never before seen.”

Citing the authoritative book Patek Philippe Genève Wristwatches by Martin Huber and Alan Banbery, Reardon says, “It’s clear that this is the third in the evolution of automatic movements from Patek Philippe.” Reardon continues: “We all talk about the 12”’600. And there are collectors obsessed with the 27-460. But the third, the sort of bronze medal, goes to the 350. And nobody talks about that. The cal. 350 is like the segue to the later cal. 310, which was the base design of numerous automatic movements today from Patek Philippe. So a cal. 350 deserves to be in a collection, as long as you can find a watchmaker who can fix it.”

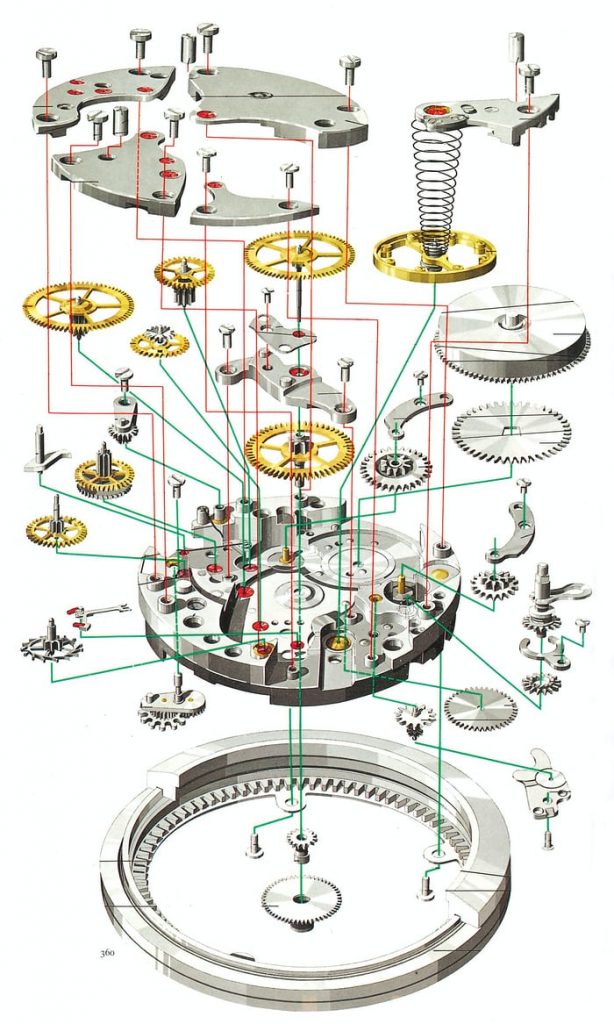

Caliber I-350 measures 28mm in diameter and a quite thin 3.5mm from top to bottom, while providing displays for the hours, the minutes, and direct central seconds. It used Patek Philippe’s proprietary Gyromax balance and vibrated at 21,600 vph. The original cal. 350, on which I-350 is based, features bi-directional winding, which apparently presented some problems, as it had to be updated. Cal. I-350 was the improvement, with its transition to unidirectional winding. In talking to dealers and other experts, the main criticism that I heard again and again was of the backwind system, also seen in certain LeCoultre watches, and its tendency to let in moisture. Whereas all the LeCoultre backwinders were manually wound, Patek used it to accommodate the winding system.

Whatever view one takes of these early peripheral winding watches, one will likely agree that the 1970s weren’t exactly a halcyon period for Swiss mechanical watchmaking. Perhaps this is why Cal. 350 and the later Cal. I-350 aren’t remembered as warmly as some of the movements that preceded and followed them. Still, these peripherally winding calibers with rotors mounted on ball bearings were the first of their type, plenty of them were made and owned, and many have survived to this day, allowing them to be found readily in the vintage market. They represent an important first in the history of watchmaking, given the subsequent rise in popularity that the peripheral rotor has seen in the last decade as well as a key step in Patek Philippe’s development of automatic movements. They also happen to be paired, by virtue of the ’70s and ’80s timeframe in which they were manufactured, with some really interesting cases, dials, and bracelets. And, of course, because of the back-mounted crown, they are all perfectly symmetrical and easy to wear for both righties and lefties. If ever a movement design was suited to the Ellipse or the Golden Circle, well, this was it.

If you like avant-garde watch designs from this period, then these are watches you will want to know about. One vintage expert I spoke to told me that he thinks these backwinders are probably undervalued, and looking at watches currently available online, I am inclined to agree.